Censorship & What Can We Learn From Japanese Shunga?

Censorship & What Can We Learn From Japanese Shunga?

In this article Japanese anthropologist Maiko Kodaka explores the relation between the historical censorship of japanese erotic art Shunga and the censorship of sexually explicit or suggestive content on social media, as things closely linked to western christian values. Maiko explains why it is so important to pay attention to these similarities and what we can learn from Japanese Shunga.

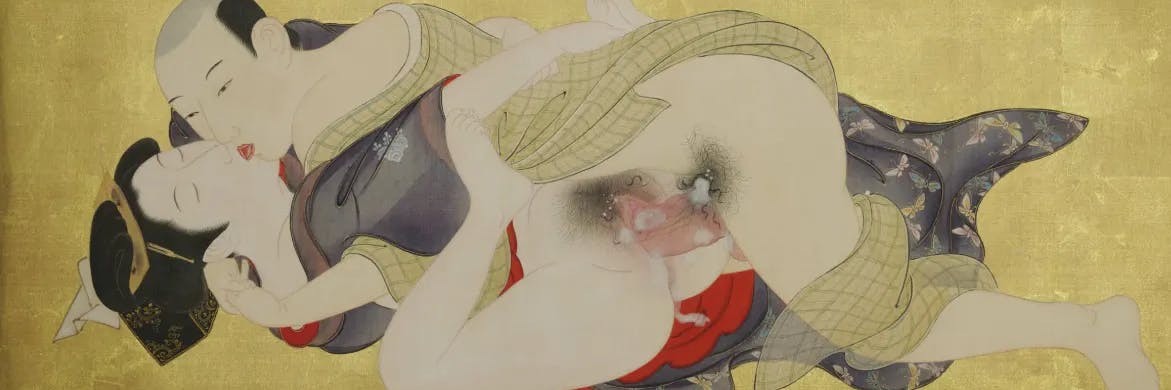

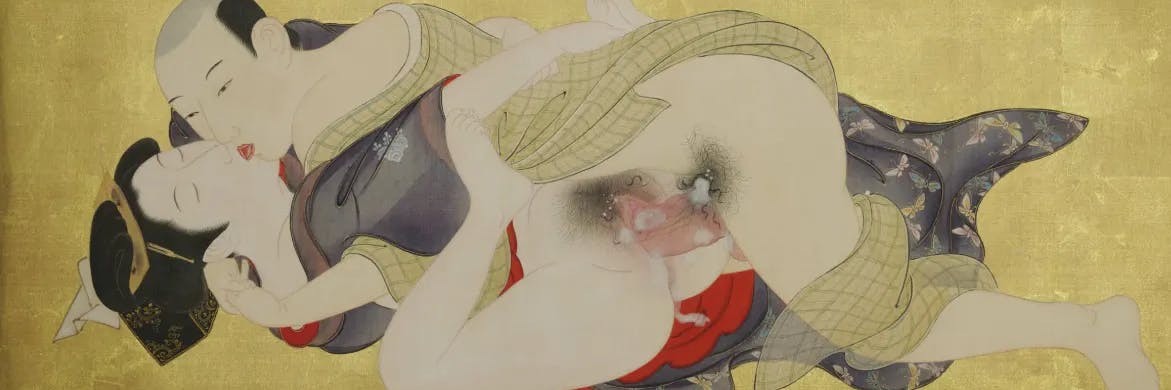

In this article I am going to explore the relation between the historical censorship of japanese Shunga and the censorship of content on social media, as things closely linked to western christian values. Shunga is a genre of Japanese modern art which depicts sexually explicit scenes, often in the form of wood carvings or paintings. The word “Shun” means spring, a nod to the fact that Shunga is a celebration of fertility. This art from, which transcended gender and social class to become hugely popular during the Edo period (1603- 1868), was also sometimes described as “Warai-e” (humorous pictures) and “Makura-e” (pillow pictures) depending on the content. Although Shunga has come to represent the aesthetics of the Edo period, shrines depicting genitals, designed to promote the fertility and prosperity of descendants can still be found all over Japan.

Whilst the genesis of Shunga is contested, leading figure in Shunga reaseach, Aki Ishigami (2015), argues that the art form most likely developed from both the chinese tradition that celebrates sex as the origin of the universe and the modern japanese idea of sex as something pleasurable. Despite covering what are typically thought of as taboo subjects, the immense popularity of this kind of art meant that even the most famous painters of the time took up the mantle. The prohibition of Shunga after the Kyōhō Reforms of 1736 did little to diminish its popularity. Instead of fading into obscurity, it became a huge underground market, with bold artists, unperturbed by government sanctions, producing increasingly luxurious Shunga is an array of rich colors and techniques.

This changed however when Commodore Perry from US arrived in Japan for a diplomatic and militaristic expedition in 1853. Despite the prohibition on the publication of Shunga, the art form remained so popular that the Japanese Shogun gave a beautiful Shunga painting as a diplomatic gift to the visiting American; something that was truly shocking to western eyes, due to its sexually explicit imagery. This story highlights the cultural conflict between Japan and Western countries. For western people who were influenced by Christianity which stigmatized sex, it must have been beyond their understanding to see Japanese people enjoying Shunga casually.

This cultural tension, alongside the western colonial influence on the changes in Japan’s political and social changes, led to the widespread banning of Shunga on the grounds that it was inappropriate for a ́modernized nation ́. For the japanese government modernization had little to do with industrialization but rather signified a move towards western ideal, and in particular the western idea of obscenity. The link between this type of modernisation and the rise is censorship is further shown by the fact that the prohibition of Shunga was rapidly accelerated, especially after Japan’s victory of the Rosso-Japan war which symbolized Japan entering members of modern nations.

Since then and despite its significance to the history of the Edo period, Shunga has been heavily stigmatized in Japanese society. When the Japanese art historian, Yoshikazu Hayashi published a book including some Shunga pictures in 1960, he was hounded by police and eventually found guilty of obscenity. This served as a warning to those in Japan still interested in Shunga and as such the medium was left untouched until 2013, when the British museum conducted their very first Shunga exhibition to mark 400 years of UK Japan diplomatic relations.

The exhibition Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art was curated by academics from both Japan and Europe, who provided detailed descriptions and analysis of the works on display, allowing viewers to foster a deeper understanding of their origin and meaning. Despite the dizzying success of the exhibition, which saw the museum reach record numbers of visitors, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art was also criticized for contributing to the stereotype of Japan as a hypersexualised culture. This obsession with Japan and sex, derived partly from an over emphasis on Hentai, was something latent in the conversations surrounding Japanese culture even long before the exhibition began, and unfortunately many visiting the exhibition where unable to shake the orientalist gaze.

The success of the Shunga exhibition at British Museum, reignited passion for the art form with many people calling for it to be recreated in Japan. Unfortunately, this enthusiasm was not reflected in the Japanese authorities cynical understanding of Shunga and more than 20 museums in Tokyo declined invitations to host the exhibition due to fear of police interference. In September 2015 after years of setbacks Japan hosted its first Shunga exhibition in a private museum owned by former prime minister, Moriteru Hosokawa. The exhibition drew lots of attention from the press, with major Japanese major newspapers and magazines clambering to feature Shunga and celebrate the groundbreaking new exhibition. However, this was not the end of the censorship of Shunga and when Shukan Bunshu published a special report on Shunga with three Shunga gravures, the chief editor, Manabu Shintani was prosecuted for a lack of consideration and forced to repose for three months. Whilst this was not censorship by the government, as the Constitution of Japan prohibits any censorship, police pressure and self regulation mean that de facto state censorship is possible.

What happened to Shintani fueled a nation-wide discussion in Japanese mass media about Shunga and whether it should be considered an ancient art form or a mere obscenity. These kinds of arguments about sexually explicit content of all sorts still seem to occupy most discussions around the topic. But shouldn’t we be asking ourselves an entirely different question? From a sociological perspective, the idea of dividing art into good and evil, provoking and obscene does not make a lot of sense. To consider something as obscene or not depends heavily on individual cognitions based on personal experiences. Therefore it is impossible to establish a commonly accepted differentiation between art and pornography. This approach to sexually explicit content is what leads to vague and often mislead guidelines on sexually suggestive images online. If mainstream media gets to decide what is considered obscene, it is inevitable that marginalised groups will suffer the consequences and diverse voices will be silenced as a result. The entire idea of obscenity is one of western origins. The history of Shunga makes clear that there was no idea of obscenity during the Edo period and before the western colonial influence. Nonetheless, there is a tendency in Japanese mass media to consider Shunga as something artistic, historical, and cultural again.

The discussions about the value of Shunga also had a very positive side effect. Shunga opened up discussions about sex and sexually explicit materials, especially among Japanese women, who had not been familiar with erotic materials up until this point. In fact, the majority of visitors of the Shunga exhibition were women. It was mainly women’s magazines who started to claim that Shunga was not vulgar because of its cultural and historical significance and depictions of female pleasure equal to men’s. For many women it was the first time they saw erotic material that portrayed sexually active women and female pleasure. This is a distinction between different sexually explicit images and films that is often put aside by censoring algorithms and their creators. If we would start censoring sexually explicit content that is clearly sexist, misogynist or discriminating against the LGBTQ community instead of dooming all depictions of sexuality as obscene, we could create a sex-positive environment in which people can express and explore their sexual identities openly and safely.

It has been 6 years since the first Shunga exhibition at the British Museum in London. Interestingly, Shunga became an iconic symbol of the new sex positive movement in Japan, especially after the global #Metoo movement in 2016 and the reveal of abuses and exploitations of porn actresses in the same year. Several women spoke up on Twitter about their experiences and encouraged public discussions about sex and consent. These modern discussions inherit Shunga’s ethos that sex is not something to be embarrassed about and that equal pleasure is what matters most. Sex is meant to be joyful, pleasurable, and sometimes even humorous. There are increasing voices for another Shunga exhibition from Japanese women arguing that the educational aspect of Shunga is one that benefits society as a whole and can help foster sexual liberation of women across the globe.

About the author:

Maiko Kodaka is a Ph.D. candidate in Anthropology and Sociology at School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Having been born and raised in the town of neon lights of Tokyo, her main academic interest has been the gender and sexual dynamics in Japanese society. Her ongoing doctoral research is an anthropological study of the fandom culture of female-friendly pornography in Japan, which is funded by the Sasakawa Studentship Programme. She also actively engages with writing online articles on gender and sexuality for Japanese online news magazine, SPA! and Habour Business Online.

GET A FREE MOVIE